This guide is for literature and resources for children in Stage 2 of primary school (Years 2 to 4), aged approximately 8 to 10. The audience for the guide is their parents, as children of this age may not be able to, or be allowed to, browse the library’s website on their own.

Piaget thought that children’s development depended partially on physical growth and the child’s interaction with the environment (Mooney, 2013). Vygotsky considered that social and cognitive development were interdependent: that social interactions shaped learning, e.g. through play with peers or reading with parents (Mooney, 2013). During middle childhood, children are developing their sense of self-efficacy, becoming more physically competent and more capable of abstract thought (Mah & Ford-Jones, 2012). The practical focus of STEM (the disciplines of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), where how-to and experimental books are common, encourages the development of self-efficacy through both physical and intellectual engagement with the material.

Drawing on Piaget's and Vygotsky's theories (Mooney, 2013), part of my purpose for this guide will be to help parents to inspire their children, helping the children to construct their understandings of STEM by reading and then having the opportunity to experience the theory in practice through the kits or activities in how-to books. STEM readings and activities allow authentic learning through activities that synthesise the STEM disciplines (Pandora & Fredrick, 2017, xvii–xviii). Ideally, parents should be ‘scaffolding’ with the children by giving them information that supports their ability to grasp a new concept or skill (Mooney, 2013). Arguably, girls and minority groups may need encouragement to engage in STEM and foster an interest at this age (Pandora & Fredrick, 2017, p. 46).

Middle childhood is a key period for cognitive and physical development (Ministry of Children and Youth Services, 2017), and it encompasses an increasingly sophisticated vocabulary and reading comprehension (Kuther, 2018). Nevertheless, indicators of learning difficulties become more visible at this stage (Ministry of Children and Youth Services, 2017), and children who experience difficulties in reading in their early years often do not catch up to their age peers (Kuther, 2018). This is evidenced in Australia by NAPLAN scores, which show a wide range of reading abilities in children aged 7-9 years old (Australian Curriculum, Assessment, & Reporting Authority, 2018).

By understanding the developmental stages of these children, this guide will be able to provide parents with suitable options across a wide range of reading abilities and interests. In particular, the use of graphic novels and books on the Premier’s Reading Challenge will help vary the reading level of texts provided to suit the child.

By providing a reading guide that includes both fiction and non-fiction STEM texts, parents and their middle primary-aged children will be exposed to triggers that will spark the children’s imaginations and foster hands-on exploration to whet their curiosity. By providing books with diverse characters, this will encourage all children to see themselves as future STEM professionals (Pandora & Fredrick, 2017, p. 46). The aim of this reading Guide is to open a window to these opportunities. Furthermore, by providing a reading guide that parents and children can experience together, this will enhance literacy opportunities at home, and lead to greater literacy achievement by children (Dearing, Kreider, Simpkins, & Weiss, 2006).

Nodelman and Reimer point out that "...literary texts offer children representations of the world and of their own place as children within that world. If a representation is persuasive, it will become the world that those child readers believe they live in." (Nodelman & Reimer, 2003, p. 128). Non-fiction texts, whose narratives are understood to be representations of the truth, are particularly important in this process of representations of the world becoming the believed reality of children (Nodelman & Reimer, 2003, p. 128). Histories and biographies have novel-like plots and tend to imply interpretations of featured people's motivations (Nodelman & Reimer, 2003, p. 129). Even science and nature books have plots, and photographs often used in these have disguised decision-making by the photographer about what angle to shoot from or what to leave out. Because non-fictional books claim to be non-fictional, they can reinforce ideological assumptions about individuals and society (Nodelman & Reimer, 2003, p. 129). In my book selection, I have chosen books featuring some female characters and non-white protagonists, thus reinforcing that STEM is for everyone.

Several assumptions can appear in STEM-themed literature for children, such as the primacy of the scientific method for understanding the world (Nodelman & Reimer, 2003, p. 132), and adults should encourage inquiry rather than saying that children should accept the science on any particular issue (Nodelman & Reimer, 2003, p. 132). As librarians, the inquiry-based approach with emphasis on projects and interdisciplinary focus of STEM complements how libraries teach research skills (Pandora & Fredrick, 2017, p. xix) The world has become increasingly complex, and librarians help young people grow their literacy and information skills, creating citizens of the future (Pandora & Fredrick, 2017, p. xxi).

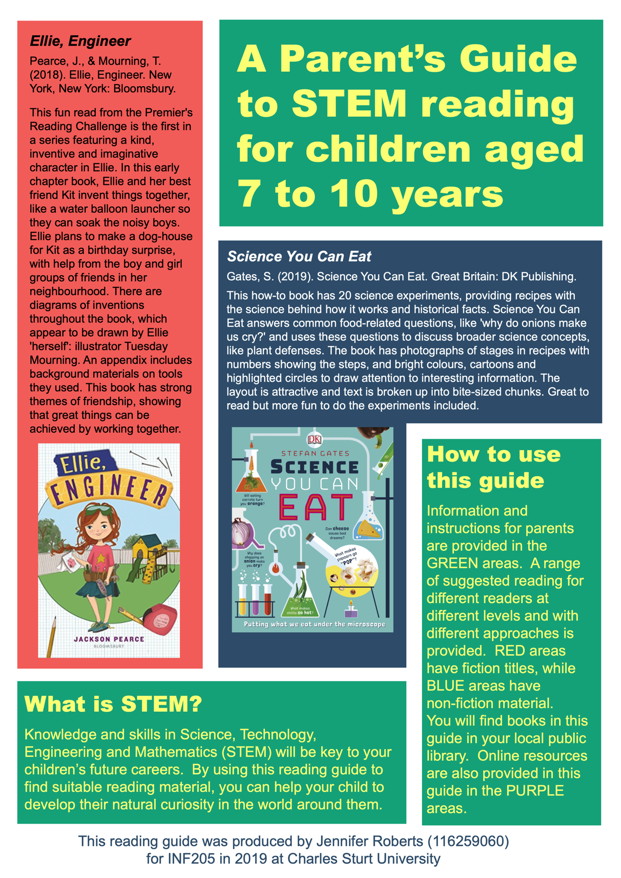

Children are often called 'natural scientists and engineers' (Tippet & Milford, 2017 p.S67), as they are inquisitive and observant. This inquisitiveness naturally lends itself to STEM explorations, from early childhood onwards (Tippet & Milford, 2017). A current trend in libraries is that they support parents in finding fun and engaging activities to do together with their children (Lopez, M. E., Caspe, M., & McWilliams, L., 2016 p. 1), and these resources aim to do so. Developing a reading guide about STEM gives the library an opportunity to support parents in exploring and developing their child's interests, particularly if the parent does not have a STEM background themselves (Petrovic, 2014). Additionally, STEM is a popular subject for library programs (Pandora & Fredrick, 2017), and science is often the largest non-fiction section in the library (Hamilton, 2009). A 'secret subject' of biographies for children is the child themselves: in retelling someone's life, the author is thinking about how the reader will be inspired by what the author has to say (Nodelman & Reimer, 2003, pp. 132-133), which is likely to hold true in fictitious biographies, such as Ellie, Engineer. Narratives that have science as a key part of the plot are better-remembered and more instructive than those where plot is added as a way to make the science more palatable (Régules, 2014). Books about science often give a glimpse into the working life of a scientist, such as At the Bottom of the World and allow readers to imagine themselves in their shoes (Hamilton, 2009).

Australian Curriculum, Assessment, & Reporting Authority. (2018). NAPLAN Achievement in Reading, Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy: National Report for 2018. Sydney: ACARA. Retrieved from https://nap.edu.au/docs/default-source/resources/2018-naplan-national-report.pdf?sfvrsn=2

Australian Library and Information Association. (2006). Statement on libraries and literacies. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/about-alia/policies-standards-and-guidelines/statement-libraries-and-literacies

Dearing, E., Kreider, H., Simpkins, S., & Weiss, H. B. (2006). Family involvement in school and low-income children's literacy: Longitudinal associations between and within families. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4), 653. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.653

Hamilton, J. (2009). What Makes a Good Science Book? Horn Book Magazine, 85(3), 269-275. Retrieved from https://www.hbook.com/2009/05/using-books/makes-good-science-book/

Kuther, T. L. (2018). Physical and Cognitive Development in Middle Childhood. In T. L. Kuther (Ed.), Lifespan Development: Lives in Context (pp. 250–281). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Lopez, M. E., Caspe, M., & McWilliams, L. (2016). Public Libraries: A Vital Space for Family Engagement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard College. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/pla/sites/ala.org.pla/files/content/initiatives/familyengagement/Public-Libraries-A-Vital-Space-for-Family-Engagement_HFRP-PLA_August-2-2016.pdf

Mah, V., & Ford-Jones, E. (2012). Spotlight on middle childhood: Rejuvenating the 'forgotten years'. Paediatrics & child health, 17(2), 81-83. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3299351/

Meek, M. (1988). How texts teach what readers learn. Stroud: Thimble Press.

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2017). On MY Way · A Guide to Support Middle Years Child Development. Toronto, ONT. Retrieved from http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/documents/middleyears/On-MY-Way-Middle-Years.pdf

Mooney, C. G. (2013). Theories of childhood : an introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget, and Vygotsky. Retrieved from Ebook Central ProQuest database.

Nodelman, P., & Reimer, M. (2003). The pleasures of children's literature Third ed. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Pandora, C. P., & Fredrick, K. (2017). Full STEAM Ahead: science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics in library programs and collections. Santa Barbara, California: Libraries Unlimited.

Petrovic, A. H. (2014). A Parent's Guide to STEM. Retrieved from https://www.inl.gov/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/A-Parents-Guide-to-STEM-English.pdf

Régules, S. (2014). Storytelling and Metaphor in Science Communication. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature, 52(3), 86-90. https://doi.org/10.1353/bkb.2014.0107

Tippet, C. D., & Milford, T. M. (2017) Findings from a Pre-kindergarten Classroom: Making the case for STEM in early childhood education. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 15(Suppl 1):S67-S86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-017-9812-8